The fire that started a Victorian gender war

Paris, 1897. The Bazar de la Charité blaze killed 118 women and girls. Where were the men?

Tuesday 4 May 1897. Fabienne Bouly has been entrusted to an old family friend for the afternoon. The little girl is to accompany Madame Legrand to the Bazar de la Charité, the annual month-long charity sale where all of Parisian high society is sure to be seen selling or shopping to fund Catholic orphanages and hospitals. The place is packed, the pope’s envoy was just here. There are duchesses, countesses and marchionesses everywhere you look, even a princess. Charity is mostly a woman’s job.

Fabienne looks the proper little girl of her rank in a dress of broderie anglaise and a bonnet over her impossibly long hair. But she struggles to play the part as Madame Legrand drags her from stall to stall amid the banners and pennons of a fake medieval street. The organisers repurposed a theatre set to dress up the temporary building they erected on a vacant lot in the chic 8th arrondissement. Trompe-l’oeil paintings and drapes cover the cheap wooden walls. A tarred awning protects shoppers from the elements. The shopfronts sound right out of a Rabelais novel – Au Chat botté, Au Soleil d'or, A la Truie qui file...

That alone would be an education: It’s a Paris Fabienne would never know. Baron Haussmann finished remodelling the French capital a generation earlier. The narrow lanes of the medieval town have given way to wide boulevards running in straight lines across the capital. Goodbye disease, crime and unrest. Everything Fabienne grows up around is new and a promise of progress, but nothing so new and promising as the real reason she’s accompanied the old widow – the cinematograph. Fabienne pulls her guardian as insistently as she dares toward the side room of the Bazar where for 50 centimes a piece they could see a few short films. But another of Madame Legrand's high society friend interrupts her plan. Already an elegant gentleman is ringing the copper bell and ushering the last few spectators through the turnstile. The show is about to start.

Suddenly Fabienne hears a tremendous boom. “Fireworks!” the child thinks excitedly. No. Fire. A cinema employee, she and the nation would later learn, struck a match too close to the projector’s ether lamp. The air itself exploded. Flames now run up the walls, devouring fabric, cardboard and dry wood, nothing in their way until they reach the ceiling. In seconds, the tarred awning ignites and communicates the fire to the rest of the building. Madame Legrand, stupefied by fear, holds her charge close. Burning tar falls in a fiery rain, sticking to hats and light spring dresses, and soon turning women to torches. A droplet slides down Fabienne’s bonnet, sets her hair on fire and burns a hole through her dress. Jolted by the pain, the girl frees herself from her guardian and runs to the front door. She is one of the first people out onto the street.

Outside the Bazar, passers-by and workers in neighbouring businesses rush to help. A groom puts out the fire in Fabienne’s hair with his bare hands and brings the little girl to a café across the road. She watches as men wearing the uniform of domestic service ram a car into the façade to open a breach. She watches another attempt to extinguish burning blouses and petticoats with a gardening hose. She watches as hundreds escape – bruised, disheveled, some ablaze – and the structure collapses on the rest. By the time firefighters arrive, not 15 minutes later, the fire is out. There is nothing left to burn. 125 people have died, 118 of them women and girls, one of them Madame Legrand, born Edmée Hubert, 63 years old.

The Bazar before and after the fire. (Source: Public domain. R.P. Fx Charmetant, "Livre d'or des martys de la charité. Hommage aux Victimes de la Catastrophe du 4 mai 1897", Paris, 1897, via Wikimedia Commons)

A floor plan of the site shows two small doors at the front, four at the back. There was a roughly 100-feet wide back lot surrounded by walls. Those who escaped to the back were either pulled up through the Hotel du Palais kitchen window or managed to follow the wall left and around the building back to the street. Those who went right only hit a cul-de-sac and were trapped by flames, smoke and intense radiating heat. That's where most bodies were found. Remember, there was no visibility and no one to guide the evacuation who knew the building. The floor was elevated and every exit had steps or required jumping. Women wore clothes that were highly flammable and reduced their mobility. Many were elderly.

Cowardly gentlemen and working class heroes

“How could I not remember?” Fabienne told radio listeners 59 years later. Though less known today, the Bazar de la Charité fire was as vivid a tragedy to turn-of-the-century Parisians as later the sinking of the Titanic. The press was instantly captivated. One element marked the blaze as a tabloid blockbuster – the gender and class of its victims.

Almost immediately, newspapers remarked on the gender imbalance – only five men among the 125 dead. Was the crowd that day really so exclusively female or was something more sinister at play? The tragedy was dubbed a new Agincourt, after the Hundred Years War battle when English archers slaughtered French forces and it seemed not one titled family was spared the loss of a son. But this time the victims were noblewomen and the men were anything but.

“I saw men who seemed like raving lunatics and swung their walking sticks to carve a passage for themselves,” a survivor, Mrs von den Henvel, told a reporter the next day. The progressive newspaper L’Eclair published 10 eyewitness accounts of violence, or at the very least inaction, on the part of gentlemen. “My wife cannot complain about any man, nor can she credit them: Not one helped her escape,” a wounded survivor’s husband told the newspaper. The only named source, Louise Feulard, had nothing more to lose. Her husband rescued her, then ran back into the blaze for his daughter. Louise lost them both. She was roughed up by three men, she said, and she knew their names. A young woman showed a bruise on her shoulder – a kick from a man as she was getting up from the floor. Another woman did owe her life to an unknown man: she escaped by following his footsteps as he muscled his way through the crowd. “Men more often got out with their skin than with their honour,” the newspaper concluded.

None of the offending men were named. The accusation was too bold to print. Even the investigating judge, Mr Bertulus, did not want to know:

“Whenever witnesses stray from the object of my inquiry and rail against men whose cowardice failed them, whose brutality sometimes delayed their escape, I stop them immediately. I’m not here to investigate matters of morality or honour. I refuse to hear the names of men who showed such a lack of courage. To save one’s neighbours, to sacrifice oneself is not a mandate; to abandon women and girls is not against the law.”

The gender war turned class war. The shortcomings of gentlemen were set against the heroism of working-class men. The kitchen staff at the neighbouring Hotel du Palais took a sledgehammer to a barred window overlooking the back of the Bazar and pulled more than 100 women to safety. The cabman George, the plumber Piquet, the roofer Desjardins… were all spotted running into the flames time and time again, each time pulling a woman out alive.

Some political context if you want it

In May 1897, France is governed by an alliance of moderate Republicans attempting to work with Catholics who had recently “rallied” to the Third Republic. But the regime, only 26 years old, is unstable and the country profoundly divided. Remnants of the Ancien Régime nobility and the conservative bourgeoisie are deeply Catholic and unconvinced by the republic. They oppose attempts to fully separate Church and State (we're 8 years away from that law). The urban working class, along with progressive allies in the professional class, defend secularism and republican values, some more radically than others. The violent repression of the Commune uprising in 1871 is still a deep wound. Anti-parliamentarism, anti-colonialism and antisemitism exist both on the left and the right, creating a complex landscape of many political confessions and their associated newspapers in a golden era for the partisan press. The Bazar fire is mere months before the Dreyfus affair, when those camps will become entrenched and all attempts at reconciliation will collapse. French historian Michel Winock called the fire “a foretaste of apocalypse.”

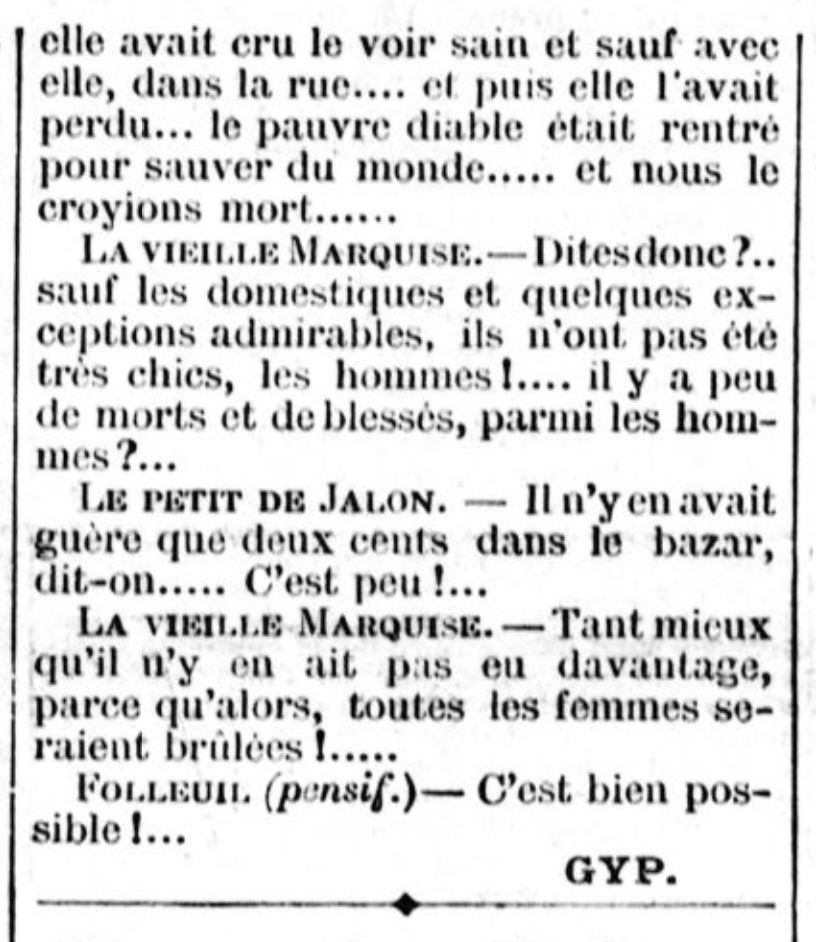

Today’s readers may have more compassion for men who panicked or looked to their own safety in a terrifying situation. But in a world still strictly defined by gender and class, wealth and status were justified by a presumption of moral and intellectual superiority. If upperclass men started behaving like street rabble, the whole social order was put into question. Soon the conversation was not about what tragedy had befallen women, but what meaning men could assign to it.

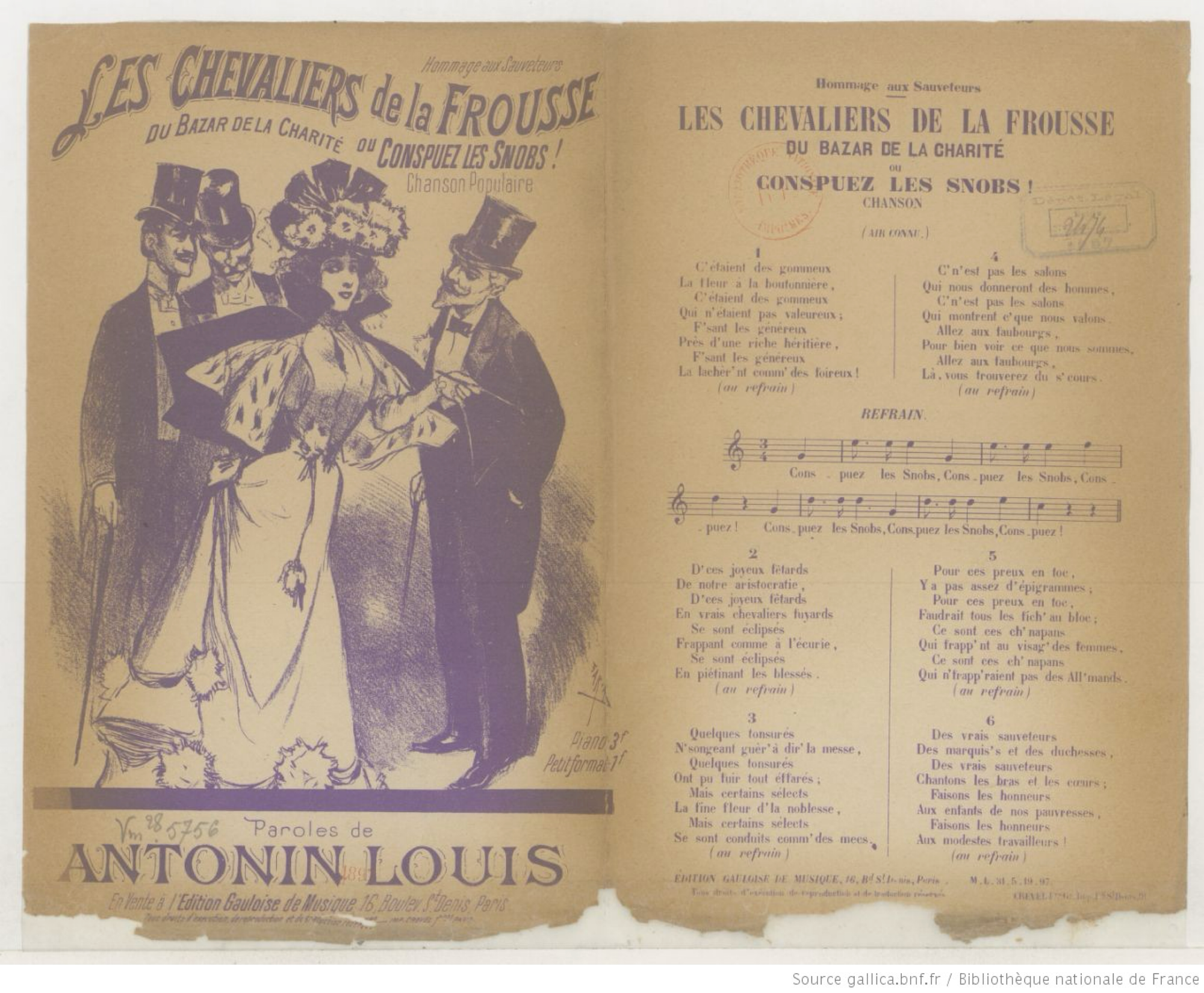

The political storm that surrounded the fire raged in newspaper articles, songs and sermons. The republican press rebuked calls for national solidarity in mourning; they lamented that the deaths of high-society women were marked by weeks of grief-stricken coverage, while the nation remained indifferent to lethal mine accidents that killed just as many. For weeks, newspapers published hagiographies of working-class heroes, even organising a large banquet for them. Radical politician and future president Georges Clémenceau wrote in an influential article:

“See these proper young gentlemen hitting panicked women with their canes, with their boots, only to cowardly run from peril. See these servant rescuers. See these workers, come by chance, heroically risking their lives, like the plumber Piquet, who saved 20 fellow humans and, fully burnt himself, returned to his workshop without saying a word. Meditate on that if you can, last representatives of the degenerate castes and bourgeois rulers of the class spirit.”

Perhaps an attempt at appeasement from the authorities, 232 people received medals – policemen, firefighters, medics, stable hands, street sweepers, printshop workers, domestic servants, cooks, café waiters, and so on. Only 14 of them were women despite the many reports of heroic action and abnegation inside the building. Meanwhile, the conservative press focused on remembering victims, sometimes with extreme pathos, insisting of religious motifs of martyrdom. It noted the same rescuers only to emphasise solidarity across society and the devotion of "small folk", denying the idea of class warfare. It attacked the opposing press which, "under the pretence of glorifying small folk, slander those who weren't lucky enough to be born a plumber."

Tensions reached fever pitch at the national funeral held at Notre Dame four days after the fire. With President Félix Faure and his secularist government in the front row, Dominican preacher Marie-Joseph Ollivier delivered a scathing sermon. “No doubt (God) wanted to deliver a terrible lesson to this arrogant century,” he proclaimed. “France deserved this punishment for it abandoned its traditions.” The provocative speech, which turned the victims into martyrs against progress, secularism and the Republic, got Ollivier fired from Notre Dame. Nonetheless, it represented a non-negligeable current in French conservatism and the debate persisted for weeks, all the way to the parliamentary floor.

And women in all that?

Women's voices in this controversy were so few I can count them: four female columnists wrote a handful of articles. Though the vast majority of people present at the Bazar were women, most eyewitness accounts in the press are from men. The objectification of victims began as soon as the blaze had extinguished their screams. Newspapers seemed to relish in describing what fire did to women’s bodies with a level of scatological detail only appropriate to a forensic pathologist’s report. I will spare my own readers. They depicted families and servants stepping over charred bodies or poking at them with a stick to get a better look at a ring or a clump of hair. Many could only be recognised by a sliver of underwear left unburnt, a chance for more prurient descriptions. At the end of the scene, the woman was often named and bared for millions of readers.

At the other end of this spectrum, victims were sublimated as martyrs, celebrated as symbols more than individuals. The Duchess of Alençon, sister of Austrian empress Sissi, was the fire's most famous victim and soon its glorious icon. A nun who survived recounted her last moments: “Go! Don't worry about me, I'll be the last one to leave," she told a young woman as she organised the evacuation. When finally there was no escape, a nun fell at her feet: "Oh Madame, what a horrible death!" To which she responded: “Yes, but think that in a few minutes, we will see God!" The story does not say how the narrator could have seen this and yet survived herself.

Most absent of all are not the victims, but the hundreds of survivors, some with life-long injuries, all undoubtedly with unimaginable trauma and with stories worth telling. Contemporary press coverage mentioned many, if only to reassure society that they were safe. They then quickly disappeared from both journalism and academic literature. There has been no research in survivors' diaries or letters to illuminate us.

So did the behaviour of men cause more women to die at the Bazar de la Charité? There is no convincing evidence either way. Authorities chose not to investigate. The press was split and too partisan to be entirely reliable. We're not even sure how many people were at the Bazar, somewhere between 700 and 1,500. We do know the vast majority of the crowd were women. We know their clothes were impractical and highly flammable. We know the building was a death trap. We cannot discount individual acts of panic.

The controversy mostly died down after two weeks, when Le Gaulois, a newspaper friendly to the upper classes, published a long investigation exonerating the gentlemen. The republican press then turned against the survivors accusing them of choosing their class over their sex:

“These ladies know that the individuals with whom they associate and whom they marry to their daughters are the most cowardly, the most abject, and the most despicable men imaginable; but, in the interest of religion and aristocracy, they will continue all the same to pretend they believe in their respectability.”

"Feminists, you reap what you sow!" An 1897 culture warrior

If well-bred young men hadn’t lived up to the ideals of chivalry, who was to blame but women? In La Nouvelle Bourgogne, on 18 May 1897, journalist M.J. wrote:

“Remember the last feminist congress where all those ladies, booed by the men, claimed that gentlemen’s politeness toward them was insulting? ‘No more protectees, no more protectors,’ they chanted.

French gallantry was to them only sentimentality, pettiness, favour, an accusation of weakness, almost an insult.

You reap, ladies, what you sowed.

The young men, whom you've demanded unlearn ideas of courtesy and chivalry, will treat you as you wish.

Would those young men be as craven as you say they are if you hadn't, in your skepticism and your vanity, taught them to behave towards you with familiarity and irreverence? If you didn't endeavour at every occasion to turn what was once their inclination to intrigue; if you didn't misrepresent the respect their fathers had and still have for you as some kind of disregard or impertinence; in a word, if you didn't constantly protest against the distinctive quality of our kind: good old French gallantry.”

They could not win.

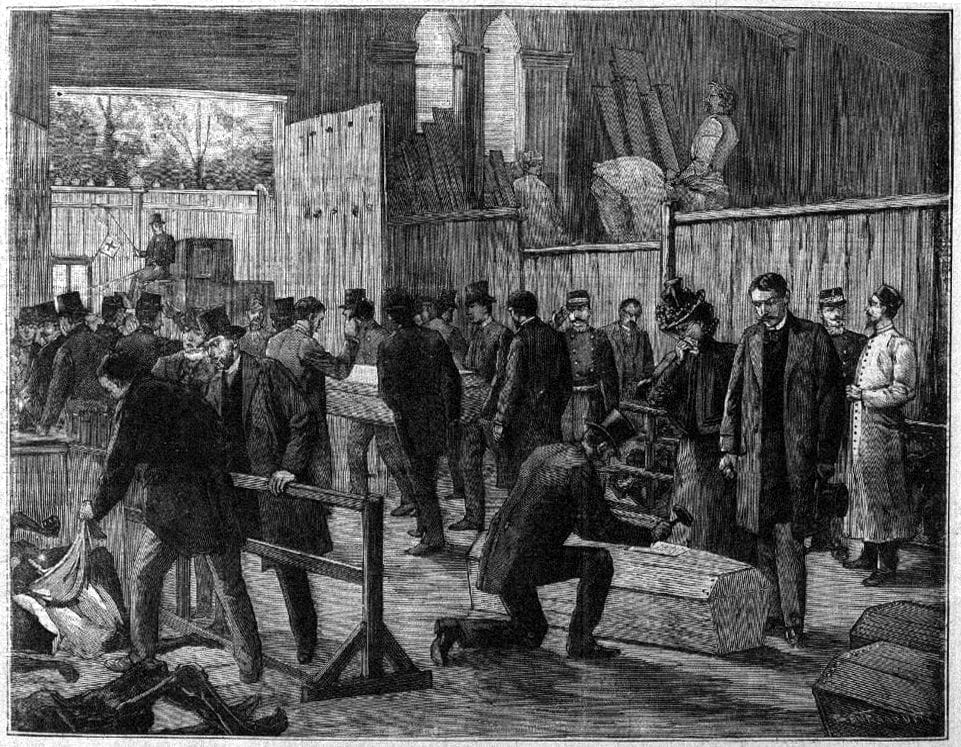

An intimate tragedy

The Palais de l’Industrie, just a block away, where the bodies are laid out for identification, is a pathetic scene the next morning. Red-eyed husbands, fathers, sons and brothers walk up and down the aisles, inspecting every mutilated corpse hoping to recognise one, two or more beloved faces. Hoping against hope not to. But it's often a female servant who cries out. She can better tell her mistress by the buckle of a boot or the stitch of a corset.

It is hours before a woman spots the little girl with the burnt hair alone in the café and leads her by the hand to the rallying point. As they turn the corner in view of the Palais de l'Industrie, there under the porch Fabienne sees her father and leaps into his arms. He had been looking for her among the dead.

Learn more

- TF1 and Netflix produced a miniseries a few years ago (Le Bazar de la Charité, English title: The Bonfire of Destiny). The first episode is a pretty accurate – and harrowing – reconstruction of the fire itself. The rest is a fiction but fairly representative of the social constraints on women's lives during the Belle Epoque (i.e. the Victorian era in Britain or the Gilded Age in the US).

- I owe a large debt to Jules Huret, a long-gone reporter at Le Figaro (my own alma mater), who covered the fire and gathered everything he knew and had witnessed in a 200-page book.

- There isn't a modern non-fiction book I could find about this. What I wrote above is probably the longest account of the Bazar de la Charité fire you'll find online and in English outside academic literature. My bibliography is available on request.

An overdue story for Leyton Midland Road Overground station

Last week, in my guided tour along the Suffragette line, I cheekily passed when I got to Leyton Midland Road. "Locals, advise," I wrote. Well, they did. The Waltham Forest Archives kindly reached out on BlueSky...

Great read by @isabelleroughol.com! Re: Leyton Midland Road query, Fletcher Lane north of station is named after former Mary Fletcher Memorial Church at High Road corner. Methodist preacher Mary Fletcher (1739-1815) was born in Leytonstone. Thanks to @wfwalkingpast.bsky.social for street name info.

— Waltham Forest Archives (@lbwfarchives.bsky.social) November 24, 2024 at 7:31 PM

[image or embed]

Mary Bosanquet Fletcher (1739-1815) was a Methodist preacher who is credited with convincing John Wesley, one of the founders of the church, to allow women to preach in public. She was born to wealth and privilege in Leytonstone, her father one of the greatest merchants in London. It was a servant in the family home who introduced her to Methodism when Mary was about 7. The servant was dismissed, but the seed had been planted.

Mary rejected a luxurious lifestyle and used her family's wealth only to help others. She opened an orphanage and school first in Leytonstone, then in Yorkshire. It was there she and her friend Sarah Ryan started preaching. In 1771, Mary wrote to Wesley defending her preaching and arguing women should be allowed to if they felt an "extraordinary call" or had permission from God. Wesley seems to have been convinced not just out of principle – though he was raised by an impressive intellectual mother – but also out of cold realism: Women were successful at making converts and Mary was particularly popular.

John Fletcher confessed his feelings for Mary a stunning 25 years after first meeting her. She married at the biblical (for the time) age of 42 in 1781 and the Fletchers became a popular preaching couple. Sadly not for long, as John died after only four years of marriage. A lesson, if ever there was one, in not delaying speaking your truth. Mary continued to preach until just a few months before her death in 1815. She was known as a "Mother in Israel", an honorific used to denote her influence in spreading Methodism across England.

There's Leyton Midland Road's history restored.

Hey, you read to the end!

Don’t miss future articles like this one; let me into your inbox.