“We don't really mean the world when we say the world.”

And we've stopped even noticing it.

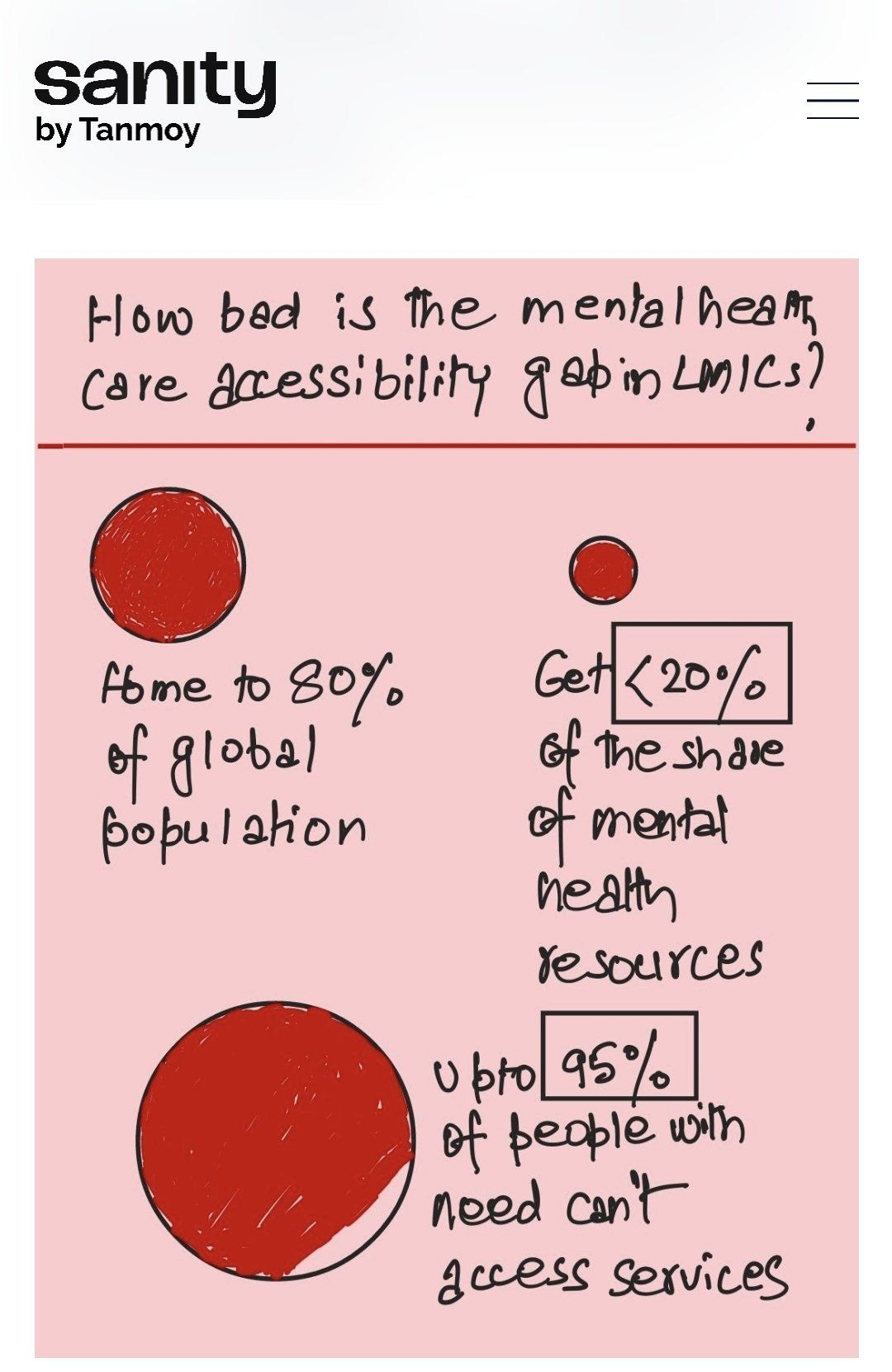

Sanity by Tanmoy is a platform dedicated to independent journalism on the politics, economics, and culture of mental health, with a focus on underrepresented communities in low- and middle-income countries. I loved Tanmoy's writing about why we need to stop worshipping at the altar of empathy, the medical gaslighting of women or his gut-wrenching essay about his fear of passing depression on to his son. Tanmoy hosts an important conversation and does so as a solo media entrepreneur with no safety net, currently on his second bout of covid. Please do subscribe and support him.

The romantic view of the pandemic was that it had given us the time to reflect and reconnect with our emotions. But three years into this hell, it is clear that the world has spectacularly failed to reflect on what matters the most. The result? More than half the world's population – our half – has been pushed into a corner where the only viable emotion is not sadness, not weariness, not affection for our shared fragile humanity, but great anger.

Let me explain with two headlines that caught my eye during my downtime this week, published in two international media behemoths: Bloomberg and Fortune. They tell you a story about the absurdity of living in a 'world' where the definition of the word is shrinking with a chilling matter-of-factness.

Did 'the world' really hit 10 billion vaccine doses?

According to the latest data from the Bloomberg Vaccine Tracker, more than 10 billion doses of Covid-19 vaccine have been administered across the globe. That's a monumental number – more than enough to cover every person in the world with at least one dose.

But, Bloomberg quickly points out, what that number hides is a lopsided map of the 'world'. Thanks to grotesque vaccine inequity, rich countries have managed to achieve deep levels of vaccination in their populations, even as poorer countries struggle to protect their people.

"The wealthiest 107 countries in the world — including China, the U.S. and Europe — comprise 54% of the global population, but have used 71% of vaccines," Bloomberg says. "Less wealthy places such as India, much of Africa and parts of Asia make up almost half of people on Earth and yet account for less than 30% of shots given."

This news comes on the back of revelations that at least 100 million doses of the vaccine that rich countries sent to poorer countries could not be used because the former suddenly released them too close to the expiry date, overwhelming the latter's storage and distribution infrastructure.

“If I was delivering a bottle of milk to you every day, you drank that bottle of milk," explains Peter Singer, an advisor with the WHO, in an interview with Global News Canada. "If one day I showed up, without any warning, with 100 bottles of milk that expired at midnight, you wouldn’t be able to drink them. That's exactly what happened here."

Bioethicist Kerry Bowman says the attitude smacks of rich countries wanting to dump 'hand-me-down rejects' on poorer countries instead of setting up a respectful partnership for the benefit of all human beings.

The travesty doesn't end there. New estimates suggest that by March, another 240 million doses held by the US, UK, Japan, Canada, and the EU could become unusable. "The number of potentially wasted doses could climb to 500 million if other countries receiving donated doses don’t have enough time to administer them."

To be sure, I am among the small elite in the global south to have received two doses of the vaccine, which has helped me avoid hospitalisation or a much worse fate. But given the virus's ability to mutate and the unabated trend of vaccine colonialism, it's impossible for even the most privileged to feel a lasting sense of safety.

Remember that slogan we were chanting in the early days of the pandemic: No one is safe until everyone is? I could throw quote after quote from global health experts at you to prove just how far we are from that goal.

Here's epidemiologist and global health researcher Madhu Pai:

"Triple-vaccinated people in the global North are rushing to declare the pandemic over when ZERO (0%) of low-income country populations are triple-vaccinated."

And here's Winnie Byanyima, executive director of UNAIDS:

"The way to end a pandemic is to close inequalities. Yet rich countries have taken the opposite path, to expand inequalities via vaccine nationalism."

But no matter how many elegantly worded indictments of vaccine inequity we serve up, we'd only be jabbing away at just one symptom of a far bigger challenge: whose globe is it anyway when we celebrate big 'global' milestones in our fight against the pandemic? And which lives do we continue to value more than others amid all the grand talk of building a better world once all this is over?

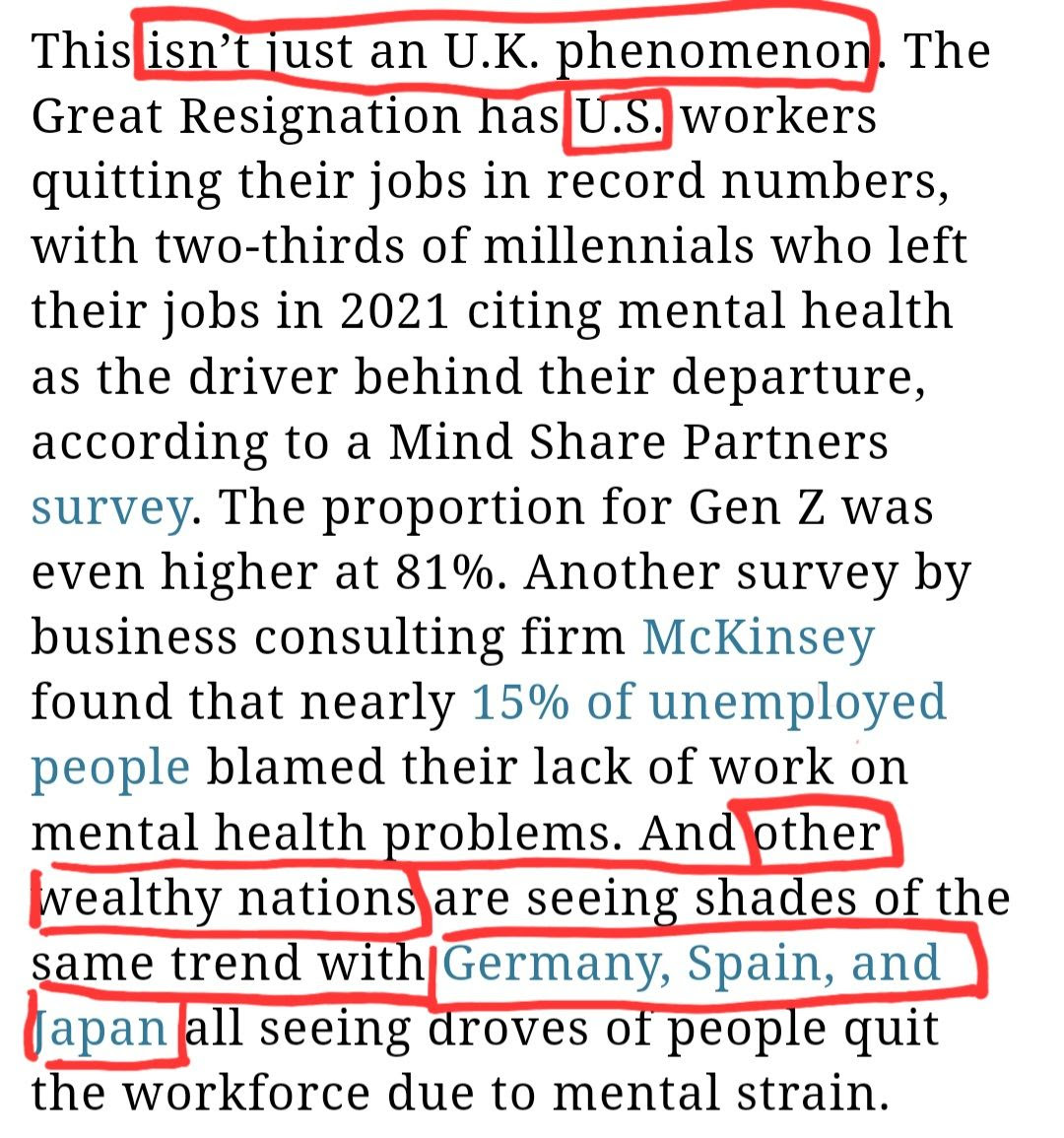

Are people 'across the world' really quitting jobs for the sake of mental health?

Which brings me to the second story, from Fortune (full disclosure: I worked at the magazine's Indian franchise many years ago). To be fair to them, a variation of the same story has appeared in virtually every business publication in the past six months. It is an attractive story with a compelling theme called The Great Resignation.

The term was coined by US management professor Anthony Klotz in mid-2021. His prescient thesis was that in the aftermath of the pandemic, employees fed up with the lack of worker protection, wage stagnation, and rising cost of living will voluntarily quit their jobs in large numbers.

But since then, what was supposed to be a purely rich country construct has been overlaid on every story about the 'global' future of work with complete lack of nuance – as if people everywhere in the world are dropping off the employment system to tend to their mental health.

Fortune's story illustrates the limits of this exaggeration. "Pandemic-driven depression is driving labor shortages around the world," announces its headline, but by way of examples the story supplies the experience of only five super-rich countries: the UK, the US, Germany, Spain, and Japan.

This is not 'the world'. It's a club.

Five wealthy countries don't make up the world. That's just a club.

There are two damaging fallouts from headlines like this. The first and most direct one is that they caricature and erase out of existence the struggles of the vast majority of the world's working population labouring without any social security.

This fantastic narrative that workers 'around the world' are quitting to prioritise their mental health is so obviously wrong that it's tiring to even point out counterexamples of devastating economic ruin and unemployment from Asian and African countries. Here's just one voice from a ground report by Kwame Anthony Appiah in the Guardian that has stayed with me:

“There are days when you wake up in bed and you think to yourself, ‘I’m tired of this.' And one minute later you think, ‘I have to do something. If I stay in bed and wallow in misery, what will the others eat tomorrow?’” – Taleni Ngoshi, a 32-year-old businesswoman from Namibia

The other, more subtle problem with articles like Fortune's is that they localise the pandemic's mental health impact in rich countries, which already hog a disproportionate share of the world's mental health care resources. By writing a story about 'depression' as a contributor to a serious economic crisis and then narrowly establishing it as a problem of a handful of high-income countries, such stories make it even harder for tragically underfunded low- and middle-income countries to claim their fair share of mental health budgets.

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are home to 80% of the global population but get less than 20% of available mental health resources.

Whether it's vaccines or resources to ensure better mental health care, a corruption has seeped into our tongues and blighted our language: we don't really mean the world when we say the world, and we've stopped even noticing it.

Next time you read a story in a powerful media outlet that blares 'the world', 'the globe', or 'the planet' in the headline but fails to see beyond a clique of wealthy countries, call it out. The world deserves better.

Noticed a change?

Borderline has new cover art and colours and will be back weekly in February with essays and episodes. Oopsie, today is February... If you're reading this online or it was forwarded to you, subscribe to the newsletter so you don't miss the new season.

Hey, you read to the end!

Don’t miss future articles like this one; let me into your inbox.