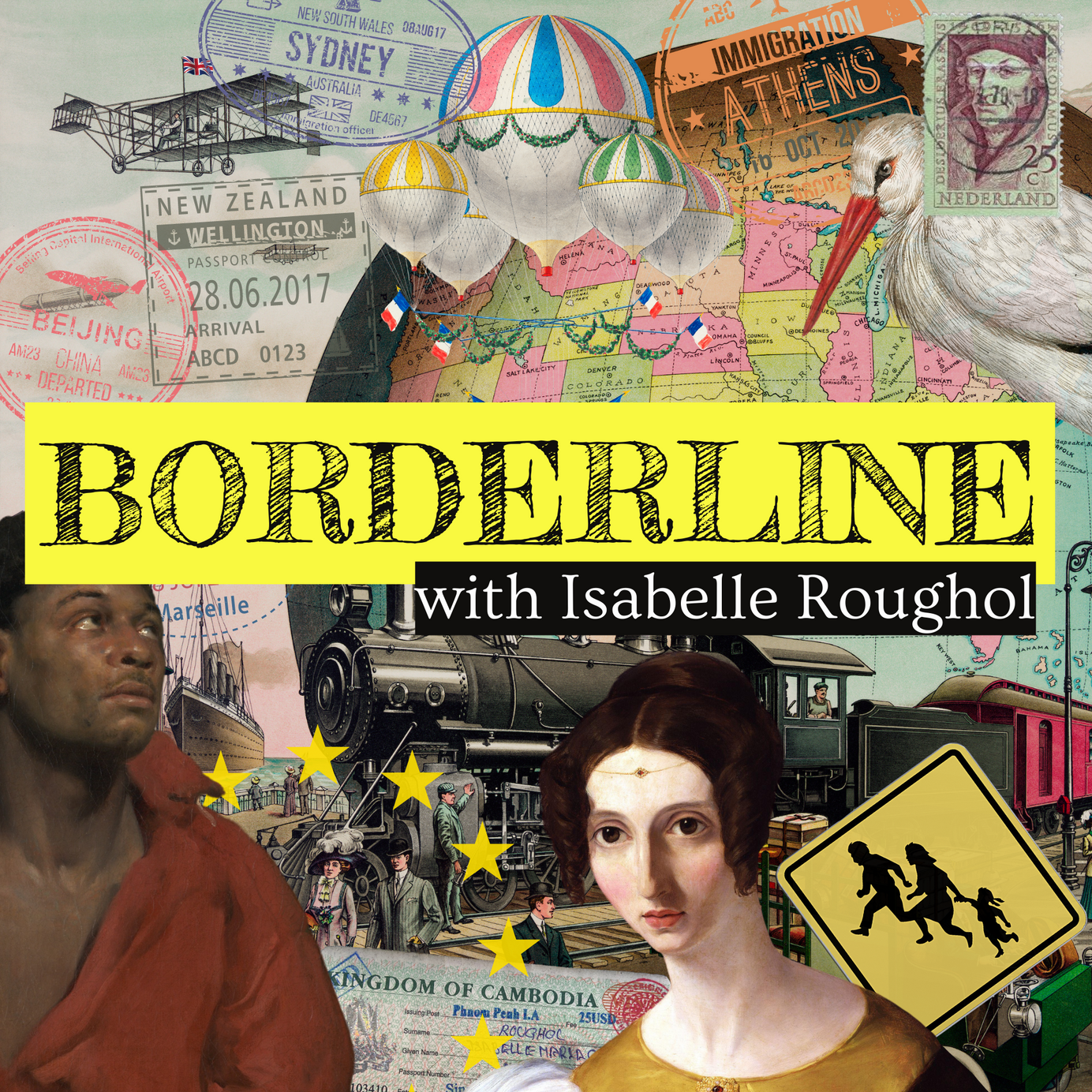

What's happening in Borderline's cover art?

Noboby asked but I'll explain anyway.

I was never a minimalist. The collage cover art for my podcast reflects a lot of me and what I hope I put into the work. If you're curious about its meaning or if you want the most detailed alt text ever, here it is.

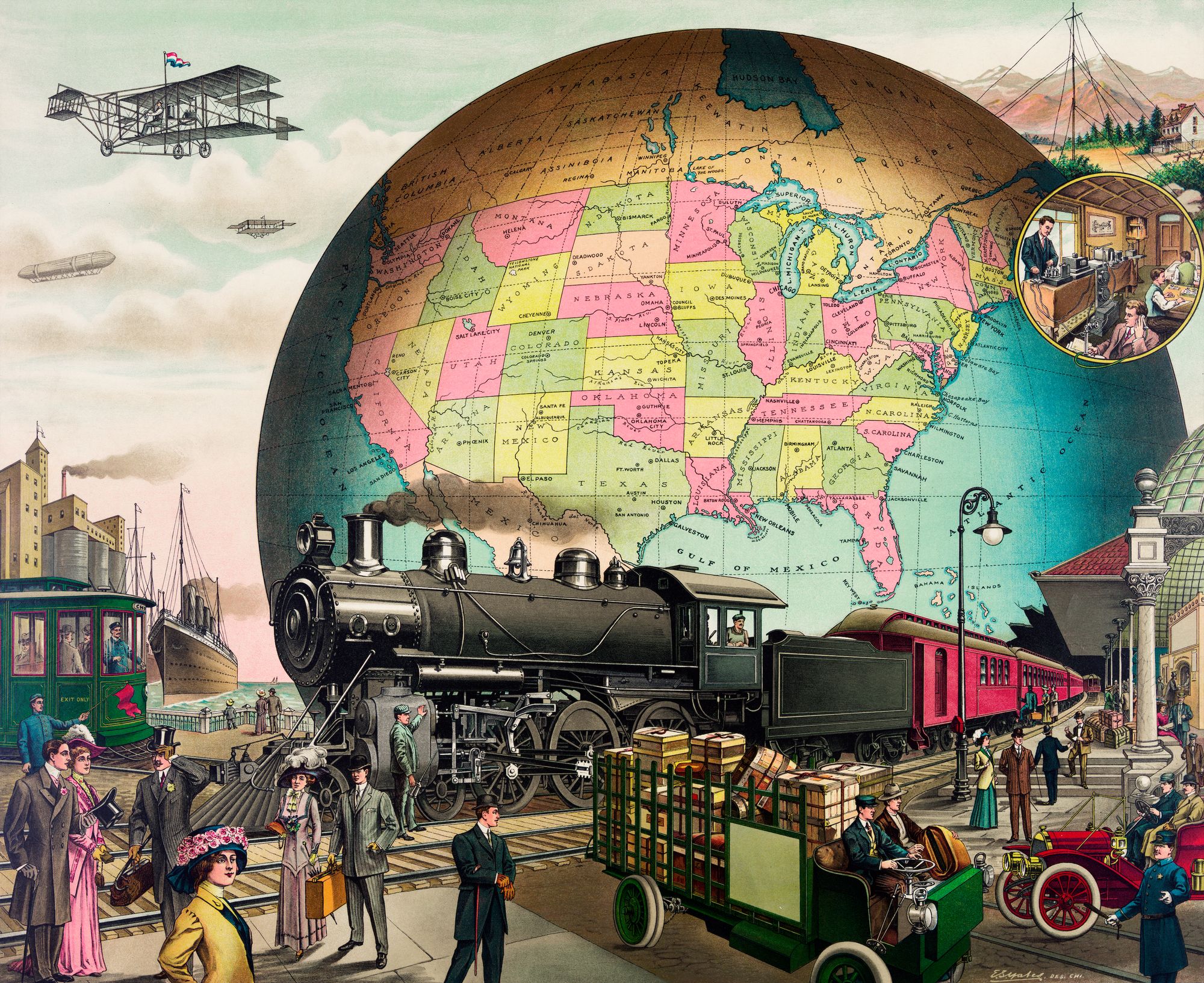

Every way you can travel

The background of the cover art is a busy picture on its own. The chromolithograph showing various 2oth-century modes of transportation and reflects my love of travel and movement. The steam train in the centre doubles as a nod to my father, a lifelong train aficionado who shovels coal into steam engines for fun. The massive globe shows the world and (some of) its borders, very much the heart of the podcast. I'm ambivalent about it being centered on the US, but it does recall the country where I learned English and spent some happy formative years. Keen eyes will notice I replaced the flag atop the plane with a Union Jack to reflect where I live and learn now – and to wave hello to the majority of my listeners.

Thespian and abolitionist Ira Aldridge

This painting stopped me in my tracks. It uses the visual codes of Christian martyrdom to paint an abolitionist manifesto. The model is as wise to it as the painter: he is Ira Aldridge, a vocal abolitionist and a celebrity. Aldridge was the first Black Shakespearian actor to win wide acclaim on the London stage. He was Othello of course, but also Richard III, Macbeth, King Lear... (See, diverse casting didn't start with the woke.) After performances he would address the audience in passionate speeches on abolition and the social ills of Europe, the United States and Africa. A true cosmopolitan, he was born American, later naturalised British and celebrated all over Europe. He died in Poland after a 70-city tour of France, just as he was planning a triumphant return to post-Civil War America.

His presence here is a reminder of the centuries-long fight for a fairer world and the power of art to break barriers. And because Aldridge was nearly forgotten after his death and this stunning painting not seen for 180 years, it also reminds me that creative success is fickle and the process must be its own reward.

Liberal and feminist icon Harriet Taylor Mill

You may not have heard of Harriet Taylor Mill, but you know her husband, John Stuart Mill. Yet Harriet was one of the great thinkers of the liberal movement in her own right and an early feminist whose writings on the perfect equality of the sexes in relationships and on the professional aspirations of women would still rankle some readers two centuries later. She was also John's equal collaborator, their conversations helping shape foundational ideas of liberal European philosophy such as the harm principle. "When two persons have their thoughts and speculations completely in common it is of little consequence, in respect of the question of originality, which of them holds the pen," Mill recognised. But the byline and posterity were his and most of her own writings were published anonymously. She's here because I'm a liberal and a feminist and I owe her a lot. Tip of the hat to Ian Dunt for bringing her to my attention.

White stork (Ciconia ciconia)

I've adopted storks as a mascot for global citizens. Obviously they're migratory birds and the wider stork family is present nearly everywhere in the world. Yet they're deeply local and connected to place. They will fly over deserts, cross mountains, forests and seas, but still return every year to the same nest. To me they were a symbol of northeastern France, where I grew up, showing up on every postcard. But they're part of the folklore and imagery everywhere from Eastern Europe to South Africa. When I'm home in Normandy, I greet a pair of them every morning in the field across the road. With warmer winters due to climate change, they've stopped migrating, but their presence signals a healthy ecosystem. In 2020, two pairs nested successfully in England for the first time in 600 years. A sign of hope...

CalTrans's migrant crossing sign

The sign depicting a migrant family rushing across the road was posted along a California highway near the Mexican border in 1990 after a spate of fatal traffic accidents. It became a pop culture icon. Some people, both pro and anti immigration, hate it passionately. But the man who designed it – John Hood, a Diné ("Navajo") graphic artist – put a lot of thought into the depiction of this family running from danger and to safety, referencing workers' rights with the profile of Cesar Chavez and the Long Walk, the forced deportation of the Diné from their homeland.

Around the world in 80 days

A hot-air balloon always reminds me of the stories I devoured as a child: Jules Verne, Jack London, Joseph Kessel... I was Buck running the Yukon trail, Patricia befriending a lion in Kenya, Natty Gan sneaking onto freight trains across America, Aronnax aboard the Nautilus. If you can hold onto the spirit, wonder and sense of adventure of a 10-year-old, life is something else. Besides, this balloon has French flags so there's home.

A few more things...

The European stars are obvious. I'm increasingly doubtful I'll see it in my lifetime but I am a bit of a federalist. The Kingdom of Cambodia visa at the bottom is straight from my passport (look closely for my name). That's another country I lived in, right after university. My final country of residence, Australia, is represented in one of the passport stamps, along with a few other places I've been. Finally the stamp represents Erasmus, the original Renaissance humanist after whom the European student exchange programme that has shaped a generation was named. There you have it.

PS: Why does it all look old?

It's an aesthetic and it looks cool, no? More importantly, everything here is in the public domain. Don't steal from artists.

Hey, you read to the end!

Don’t miss future articles like this one; let me into your inbox.